Finalist in the Wallace Art Awards 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2014

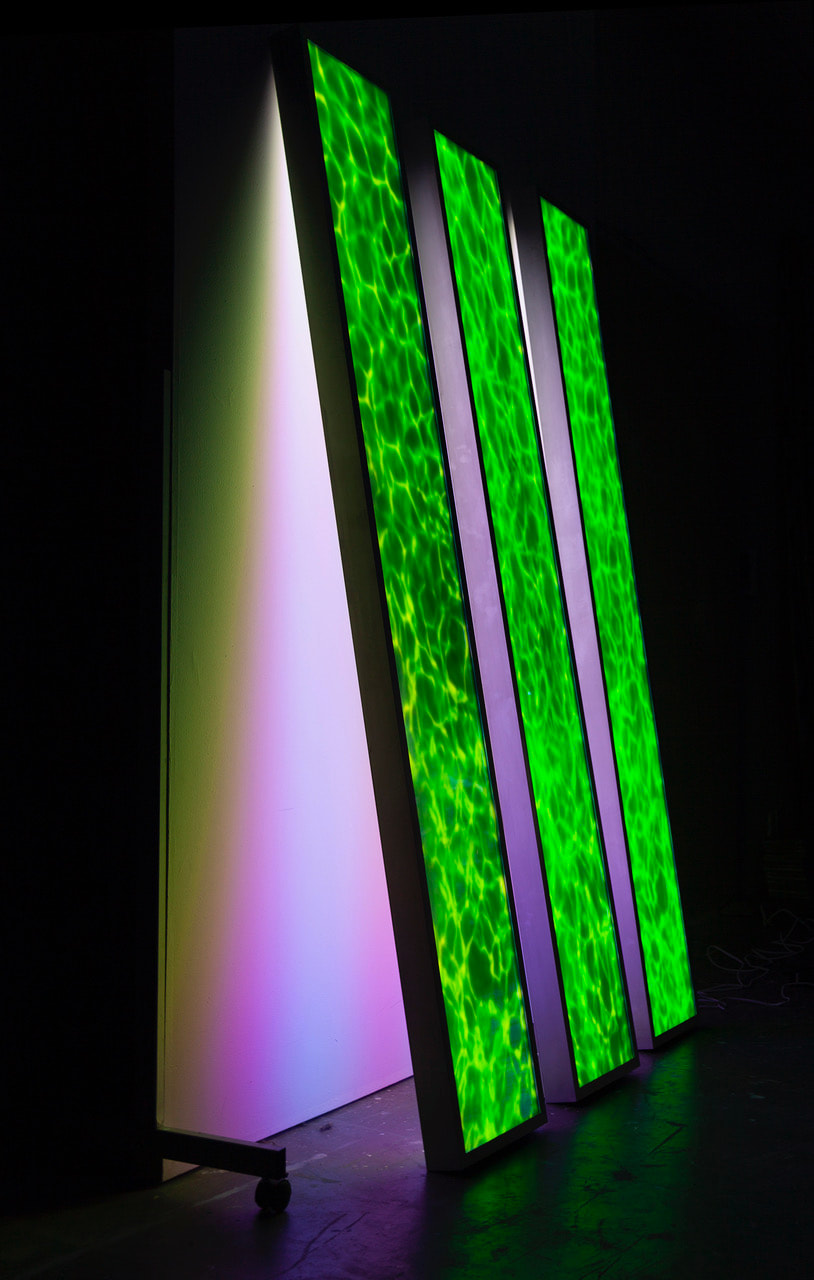

Tides, Earth, Moon & Sun, 2020

‘Tides’ is a development of my work using digital collage, lightbox and acrylic panels with dichroic film. The work continues to develop my practice focus on bodies of water and, in particular, bodies of water as we enter the Anthropocene, or the Chthulucene as Donna Harraway describes it, avoiding further embedding of Anthropic discourse itself a factor at the centre of our crisis, diminishing the non-human majority and the natural and universal forces within which we are located. ‘Tides 2020’ comprises three pieces – Earth, Moon & Sun – the three bodies which are the major influences on ocean tides

This installation extends the earlier navigational totems on acrylic panels by introducing an internal light source which seeks to creates an internal source of energy symbolic of the energy of our oceans. The light boxes also reference digital technologies and lighting as a key factor in creating an image in photography which is an element of this sculptural form. The multidimensional expression of light both facing out to the gallery and behind to the wall it leans onto expresses the multidimensional approaches and solutions we as human beings will need to take to bring our oceans back to health.

The photographic image on the face of the lightbox references the ‘age of the fishes’ (as the Devonian era was known and captures the waves of refracted light created on the bottom of the ocean when light passes from air into the transparent medium of water and the surface is in motion from wind. The backward facing surface of the lightbox that illuminates the gallery wall is representative of water that is not transparent but murky from different types of pollution and therefore rather than the poetic lines of refracted light presents light dissipated though the particles in the water in a non descriptive dull glow.

The lightbox panels lean against the wall of the gallery at an angle that brings into play the gallery wall, the light spilling out of the back of the lightbox through the opal acrylic and dichroic film glows. The mirror reflectivity of the dichroic film adds a temporal immediacy by including the viewer and the gallery space and adds another chamelian-like aspect by selectively passing light of a small range of colors through the film, while reflecting other colors. This means the work ‘changes colour’ from varying viewer perspectives and changing light conditions, mirroring properties of light on water and symbolising the changing states of our oceans. The changing colour also references algae blooms that occur due to excessive nitrates leeching from the land and which result in Red, Green and Yellow tides that create dead zones in the sea due to the oxygen being used up by the algae. The lines of light captured in the photographs represent metaphorical webs or neural networks within the ocean and our whole ecology, referencing this reconnection we will require to address our cultural and ecological crisis, known as the climate crisis.

This installation extends the earlier navigational totems on acrylic panels by introducing an internal light source which seeks to creates an internal source of energy symbolic of the energy of our oceans. The light boxes also reference digital technologies and lighting as a key factor in creating an image in photography which is an element of this sculptural form. The multidimensional expression of light both facing out to the gallery and behind to the wall it leans onto expresses the multidimensional approaches and solutions we as human beings will need to take to bring our oceans back to health.

The photographic image on the face of the lightbox references the ‘age of the fishes’ (as the Devonian era was known and captures the waves of refracted light created on the bottom of the ocean when light passes from air into the transparent medium of water and the surface is in motion from wind. The backward facing surface of the lightbox that illuminates the gallery wall is representative of water that is not transparent but murky from different types of pollution and therefore rather than the poetic lines of refracted light presents light dissipated though the particles in the water in a non descriptive dull glow.

The lightbox panels lean against the wall of the gallery at an angle that brings into play the gallery wall, the light spilling out of the back of the lightbox through the opal acrylic and dichroic film glows. The mirror reflectivity of the dichroic film adds a temporal immediacy by including the viewer and the gallery space and adds another chamelian-like aspect by selectively passing light of a small range of colors through the film, while reflecting other colors. This means the work ‘changes colour’ from varying viewer perspectives and changing light conditions, mirroring properties of light on water and symbolising the changing states of our oceans. The changing colour also references algae blooms that occur due to excessive nitrates leeching from the land and which result in Red, Green and Yellow tides that create dead zones in the sea due to the oxygen being used up by the algae. The lines of light captured in the photographs represent metaphorical webs or neural networks within the ocean and our whole ecology, referencing this reconnection we will require to address our cultural and ecological crisis, known as the climate crisis.

Seven Sisters, 2019

Alcyone – Matariki, eyes of Tāwhirimātea

Atlas – Tupu-ā-rangi, sky tohunga

Electra – Waipuna-ā-rangi, sky spring

Taygeta – Waitī, sweet water

Pleione – Tupu-ā-nuku, Earth tohunga

Merope – Ururangi, entry to the heavens

Maia – Waitā, sprinkle of water

Winner of the people's Choice Award

Materials: 7 acrylic panels, inkjet photographic print, dichroic film

Height 2200 Width 2000 Depth 100mm

Finalist of the 28th Wallace art Awards 2019

This installation extends my Oceanids series to achieve scale and affect and bring new materiality into the conversation. This series comprises symbolic portraits representing Oceanids – female eco-warriors from Greek mythology with parallels to Taniwha. Among the best-known Oceanids are the Pleiades, known as the Seven Sisters or Matariki, stars in the constellation of Taurus. Each panel represents one of the seven sisters, and the viewer’s passage past the panels is a navigational journey in space and time. These astronomical Oceanids relate to navigation and agricultural seasons in many cultures. In Aotearoa, these stars are Matariki, and their rising marks the new year for Maori. More fully, they are ‘Nga mata o te ariki o Tawhirimatea’, the eyes of the god Tawhirimatea, god of weather, thunder, storms and clouds. The panels are acrylic (PMMA) covered with a dichroic film. The acrylic, made from petroleum, provides a reflective ‘oil slick’, and presents material formed at the end of the Devonian era around 400 million years ago from collapsed coral reefs during Earth’s fifth extinction event. Today, in the midst of the sixth great extinction, we stand terrified that our unleashing of hydrocarbons will return us to the watery depths or force us into the stars to look for a new home. The imagery on the panels reference the ‘age of the fishes’ (as the Devonian era was known). I am motivated to encourage new thinking and a new navigation as we journey into the Chthulucene[1].

This installation references the minimalist painted plywood panel works of John McCracken but while his works pursue the properties of clarity, conciseness and effectiveness my work looks at properties of reflectiveness, obscurity, diffuseness and inconclusiveness to create a sense of the shifting ground upon which we find ourselves in this current time in the history of this planet. The use of reflective materials both the acrylic and dichroic film places the work in the context of the widespread and sustained use of reflective surfaces in art that arose concurrently with Minimalism and continues today. These industrially-produced materials are also associated with Minimalism, although the dichroic film is a very contemporary product. Artists that I have referenced include Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Dan Graham and Robert Smithson who use reflective surfaces and engage actively in the discourse surrounding their work in ways that should be considered “reflective” as well. The other important cultural location for this work is the Chthulucene or Anthropocene, the geological era we are entering so named because it may be the first (and only) epoch in which human activity on Earth is a critical factor. However, even ‘Anthropocene’ as a term is problematic because it continues the Anthropic discourse embeded in our crisis – hence ‘Chthulucene’ (see Harroway et al). The latter emphasises the ambiguity, uncertainty and feminine element, a return to greater connectivity to all things, including the non-human majority. Exploring mythology, like Oceanids, informs us as to how earlier cultures represented this need to protect resources and remain connected to our ecology.

[1] “I am aligned with feminist environmentalist Eileen Crist when she writes against the managerial, technocratic, market-and-profit besotted, modernising, and human-exceptionalist business-as-usual commitments of so much Anthropocene discourse….But an unfurling Gaia is better situated in the Chthulucene, an ongoing temporality that resists figuration and dating and demands myriad names.” (Donna Harraway, “Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene” from ‘Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene’, Duke University Press, 2016)

Alcyone – Matariki, eyes of Tāwhirimātea

Atlas – Tupu-ā-rangi, sky tohunga

Electra – Waipuna-ā-rangi, sky spring

Taygeta – Waitī, sweet water

Pleione – Tupu-ā-nuku, Earth tohunga

Merope – Ururangi, entry to the heavens

Maia – Waitā, sprinkle of water

Winner of the people's Choice Award

Materials: 7 acrylic panels, inkjet photographic print, dichroic film

Height 2200 Width 2000 Depth 100mm

Finalist of the 28th Wallace art Awards 2019

This installation extends my Oceanids series to achieve scale and affect and bring new materiality into the conversation. This series comprises symbolic portraits representing Oceanids – female eco-warriors from Greek mythology with parallels to Taniwha. Among the best-known Oceanids are the Pleiades, known as the Seven Sisters or Matariki, stars in the constellation of Taurus. Each panel represents one of the seven sisters, and the viewer’s passage past the panels is a navigational journey in space and time. These astronomical Oceanids relate to navigation and agricultural seasons in many cultures. In Aotearoa, these stars are Matariki, and their rising marks the new year for Maori. More fully, they are ‘Nga mata o te ariki o Tawhirimatea’, the eyes of the god Tawhirimatea, god of weather, thunder, storms and clouds. The panels are acrylic (PMMA) covered with a dichroic film. The acrylic, made from petroleum, provides a reflective ‘oil slick’, and presents material formed at the end of the Devonian era around 400 million years ago from collapsed coral reefs during Earth’s fifth extinction event. Today, in the midst of the sixth great extinction, we stand terrified that our unleashing of hydrocarbons will return us to the watery depths or force us into the stars to look for a new home. The imagery on the panels reference the ‘age of the fishes’ (as the Devonian era was known). I am motivated to encourage new thinking and a new navigation as we journey into the Chthulucene[1].

This installation references the minimalist painted plywood panel works of John McCracken but while his works pursue the properties of clarity, conciseness and effectiveness my work looks at properties of reflectiveness, obscurity, diffuseness and inconclusiveness to create a sense of the shifting ground upon which we find ourselves in this current time in the history of this planet. The use of reflective materials both the acrylic and dichroic film places the work in the context of the widespread and sustained use of reflective surfaces in art that arose concurrently with Minimalism and continues today. These industrially-produced materials are also associated with Minimalism, although the dichroic film is a very contemporary product. Artists that I have referenced include Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Dan Graham and Robert Smithson who use reflective surfaces and engage actively in the discourse surrounding their work in ways that should be considered “reflective” as well. The other important cultural location for this work is the Chthulucene or Anthropocene, the geological era we are entering so named because it may be the first (and only) epoch in which human activity on Earth is a critical factor. However, even ‘Anthropocene’ as a term is problematic because it continues the Anthropic discourse embeded in our crisis – hence ‘Chthulucene’ (see Harroway et al). The latter emphasises the ambiguity, uncertainty and feminine element, a return to greater connectivity to all things, including the non-human majority. Exploring mythology, like Oceanids, informs us as to how earlier cultures represented this need to protect resources and remain connected to our ecology.

[1] “I am aligned with feminist environmentalist Eileen Crist when she writes against the managerial, technocratic, market-and-profit besotted, modernising, and human-exceptionalist business-as-usual commitments of so much Anthropocene discourse….But an unfurling Gaia is better situated in the Chthulucene, an ongoing temporality that resists figuration and dating and demands myriad names.” (Donna Harraway, “Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene” from ‘Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene’, Duke University Press, 2016)

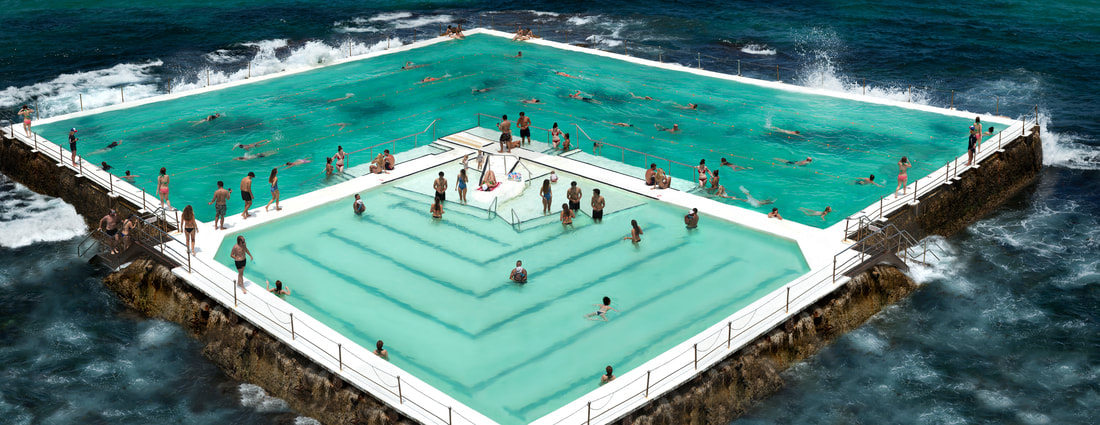

‘Icebergs 2018’

Inkjet Print on Fujitran Film

Led Lightbox

W1600 x H700mm

Finalist of the 27th Wallace art Awards 2018

Bondi’s Icebergs pool is re-interpreted metaphysically and literally as an iceberg, adrift at sea. It is a human construction now cut off from the land by the affects of sea level rise accelerated by global warming. The work re-imagines this iconic coastal swimming pool - one of many coastal pools that are a feature of NSW, having morphed through global warming in the Anthropocene into an isolated playground or watery oasis. This work is part of a continuing series within Carter's practice in which the viewer is positioned as ‘arial voyeur’. This contemporary, drone-like perspective references urban life's growing detachment from nature, both physically and psychologically, in the face of technology’s increasing encroachment on our everyday lives.

To create this work, Carter digitally paints with many photographs taken of the same scene form different angles over a period of time. In this way the relativities of time and space are manipulated to reveal the construct within which we all operate. There are many dynamics at play within this sensual space of pleasure and performance. The work examines this space of relaxation, physical exercise but also the absurdity and vulnerability of humanity in the Anthropocene, a time in which, despite all our luxury and progress, we are most at risk from our own collective behaviour. Icebergs, seeks to ‘explores boundaries between the natural and the cultural, liminal spaces and forms that are both and neither.’ (D, Campany ed, Art and Photography, Phaidon, 2008).

Inkjet Print on Fujitran Film

Led Lightbox

W1600 x H700mm

Finalist of the 27th Wallace art Awards 2018

Bondi’s Icebergs pool is re-interpreted metaphysically and literally as an iceberg, adrift at sea. It is a human construction now cut off from the land by the affects of sea level rise accelerated by global warming. The work re-imagines this iconic coastal swimming pool - one of many coastal pools that are a feature of NSW, having morphed through global warming in the Anthropocene into an isolated playground or watery oasis. This work is part of a continuing series within Carter's practice in which the viewer is positioned as ‘arial voyeur’. This contemporary, drone-like perspective references urban life's growing detachment from nature, both physically and psychologically, in the face of technology’s increasing encroachment on our everyday lives.

To create this work, Carter digitally paints with many photographs taken of the same scene form different angles over a period of time. In this way the relativities of time and space are manipulated to reveal the construct within which we all operate. There are many dynamics at play within this sensual space of pleasure and performance. The work examines this space of relaxation, physical exercise but also the absurdity and vulnerability of humanity in the Anthropocene, a time in which, despite all our luxury and progress, we are most at risk from our own collective behaviour. Icebergs, seeks to ‘explores boundaries between the natural and the cultural, liminal spaces and forms that are both and neither.’ (D, Campany ed, Art and Photography, Phaidon, 2008).

Living Water, 2017

Medium: inkjet printed onto silk

Dimensions 3200 x1000mm

Finalist of the 26th Wallace Art Awards 2017

I’ve always had a strong connection to water, and bodies of water: the ocean, rivers and lakes. Water is life, and the exploration of both the materiality of water and our human relationship with water is at the core of my work. I never feel more exhilarated or more connected to the universe than when I am on, in or near bodies of water, and this connectedness as well as a concern for the challenges of the ecological crisis facing waterways, inspires my art practice. As New Zealander’s, our identity is tied to Aotearoa‘s identity as an ecologically- isolated territory discovered by ocean borne navigators who looked to the skies and ocean currents to locate themselves. Another key dimension to my practice is an exploration of the interaction between the viewer and the art work. By this I mean experiencing ‘seeing’ as more than just observation, but as a visceral, connected, lived experience – a ‘becoming’, as French philosopher Gilles Deleuze describes it. I am drawn to the connection between the flow of water and the flow of becoming, and the connectedness of these flows.

This work is from a series of works inspired by Japanese woodblock prints, specifically the Ukiyo-e artist Hokusai’s iconic work ‘The Great Wave of Kanagawa’, (1829–1832). The Ukiyo-e genre flourished in Japan from the late 17th century to the 19th century. The term Ukiyo-e translates as ‘pictures of the floating world’. As well as being interested stylistically in theses works I have also used the form of a scroll, referencing Japanese silk scrolls or “kakejiku”.

‘Living Water’ continues to explore an interest I have in image making and the ability of photography to create illusion and to question our sense of perception. As Susan Sontag has stated, ‘the painter constructs the photographer discloses’.

This work has been created by digital collaging using five photographs captured from rocky outcrops at Tairua beach on the Pacific Ocean. Inverted, the waves reference the curved ‘fingertips’ of Hokusai’s wave. The work seeks to be both otherworldly and completely of this world.

Just as we know from Quantum physics that the act of observation affects the outcome of what is observed, so the act of observing is an experience that transforms the viewer – especially if the viewer is open to the internal worlds and reflections brought forward by the interaction with a work of art.

I believe that everything has a kind of consciousness, and this work seeks to explore both our consciousness with respect to water, but also what we might call the consciousness of water itself and the affect that ‘Blue Space’ has on us both physically and psychology.

Medium: inkjet printed onto silk

Dimensions 3200 x1000mm

Finalist of the 26th Wallace Art Awards 2017

I’ve always had a strong connection to water, and bodies of water: the ocean, rivers and lakes. Water is life, and the exploration of both the materiality of water and our human relationship with water is at the core of my work. I never feel more exhilarated or more connected to the universe than when I am on, in or near bodies of water, and this connectedness as well as a concern for the challenges of the ecological crisis facing waterways, inspires my art practice. As New Zealander’s, our identity is tied to Aotearoa‘s identity as an ecologically- isolated territory discovered by ocean borne navigators who looked to the skies and ocean currents to locate themselves. Another key dimension to my practice is an exploration of the interaction between the viewer and the art work. By this I mean experiencing ‘seeing’ as more than just observation, but as a visceral, connected, lived experience – a ‘becoming’, as French philosopher Gilles Deleuze describes it. I am drawn to the connection between the flow of water and the flow of becoming, and the connectedness of these flows.

This work is from a series of works inspired by Japanese woodblock prints, specifically the Ukiyo-e artist Hokusai’s iconic work ‘The Great Wave of Kanagawa’, (1829–1832). The Ukiyo-e genre flourished in Japan from the late 17th century to the 19th century. The term Ukiyo-e translates as ‘pictures of the floating world’. As well as being interested stylistically in theses works I have also used the form of a scroll, referencing Japanese silk scrolls or “kakejiku”.

‘Living Water’ continues to explore an interest I have in image making and the ability of photography to create illusion and to question our sense of perception. As Susan Sontag has stated, ‘the painter constructs the photographer discloses’.

This work has been created by digital collaging using five photographs captured from rocky outcrops at Tairua beach on the Pacific Ocean. Inverted, the waves reference the curved ‘fingertips’ of Hokusai’s wave. The work seeks to be both otherworldly and completely of this world.

Just as we know from Quantum physics that the act of observation affects the outcome of what is observed, so the act of observing is an experience that transforms the viewer – especially if the viewer is open to the internal worlds and reflections brought forward by the interaction with a work of art.

I believe that everything has a kind of consciousness, and this work seeks to explore both our consciousness with respect to water, but also what we might call the consciousness of water itself and the affect that ‘Blue Space’ has on us both physically and psychology.

Seaside (Waikiki), 2016

Dimensions: 1560mm x 600mm

Finalist of the 25th Wallace Art Awards 2016

wallaceartstrust.org.nz/category/annual-wallace-art-awards/

Carter’s interest in photographing seascapes centres on an inquiry as to how humans interact with the sea. Carter’s practice continues its exploration of bodies of water as physical, cultural and social ‘landscapes’. Previous work has dealt with a private perspective into Carter’s own relationship to the ocean, often from intimate perspectives in, on or under the surface of the water. This was overlaid in her Oceanids series (2014/5) with an investigation of mythological connections as part of our relationship to the sea.

This work Seaside Waikiki is part of a new series in which she positions the viewer as ‘arial voyeur’, an inherently contemporary, drone-like perspective. This provides a detachment and space to further observe our diverse relationships with the seashore. There are many dynamics at play within this sensual space of pleasure and performance. The work examines the absurdity and vulnerability of humanity within a space of sea, in particular as a space of relaxation, pleasure, leisure, escape and fantasy.

The image was created through digital collaging of of 4 photographs of the same scene, as well as collaging specific individuals sometimes twice in different positions of activity in the same space of water. This was done to make visual the relativities of time and space often experienced on vacation, the seeming slowness of time spent relaxing, and the languid movement of people between and through this liquid space. The sublime beauty of the milky, torquoise sea cradles a proliferation of humanity and their toys within its warm embrace.

Paradoxically, it is also first and foremost a space of denial, this beach being a human construction, utilising the technology of ‘beach nourishment’, common in many countries, including New Zealand. Waikiki, in the near past, was a bay of crystal clear, lime green water, revealing its many reefs along the bottom of the bay. The milky residue is the result of a white silt that continues to leach into the water from the sand deposited there as ‘beach nourishment’, obscuring and destroying the reefs and the marine life dependent on them. (Gradually, Hawaii’s iconic beaches are disappearing. Most beaches on the state’s three largest islands are eroding, and the erosion is likely to accelerate as sea levels rise.)

Beneath this sublime scene of human fantasy, is the denial of a recognition of the bioloical impact of beach nourishment, and how the creation of an ‘idyllic’ (utopian) vacation environment is a severely destructive action. Beach nourishment destroys the entire nearshore marine ecosystem affecting birds, nearshore fish, and invertebrates. Orrin H. Pilkey in his book, “The Last Beach” explains that these attempts are doomed to failure and that, “to save beaches we must let beaches go where and how they want”.

Carters work references artists like Richard Misrach and Andreas Gursky in asking fresh questions about our interactions with the natural world, and bodies of water in particular, and what these interactions mean both for our interior, personal worlds as well as our consumerist cultural and social structures as our natural world continues to be challenged under our ‘stewardship’.

Dimensions: 1560mm x 600mm

Finalist of the 25th Wallace Art Awards 2016

wallaceartstrust.org.nz/category/annual-wallace-art-awards/

Carter’s interest in photographing seascapes centres on an inquiry as to how humans interact with the sea. Carter’s practice continues its exploration of bodies of water as physical, cultural and social ‘landscapes’. Previous work has dealt with a private perspective into Carter’s own relationship to the ocean, often from intimate perspectives in, on or under the surface of the water. This was overlaid in her Oceanids series (2014/5) with an investigation of mythological connections as part of our relationship to the sea.

This work Seaside Waikiki is part of a new series in which she positions the viewer as ‘arial voyeur’, an inherently contemporary, drone-like perspective. This provides a detachment and space to further observe our diverse relationships with the seashore. There are many dynamics at play within this sensual space of pleasure and performance. The work examines the absurdity and vulnerability of humanity within a space of sea, in particular as a space of relaxation, pleasure, leisure, escape and fantasy.

The image was created through digital collaging of of 4 photographs of the same scene, as well as collaging specific individuals sometimes twice in different positions of activity in the same space of water. This was done to make visual the relativities of time and space often experienced on vacation, the seeming slowness of time spent relaxing, and the languid movement of people between and through this liquid space. The sublime beauty of the milky, torquoise sea cradles a proliferation of humanity and their toys within its warm embrace.

Paradoxically, it is also first and foremost a space of denial, this beach being a human construction, utilising the technology of ‘beach nourishment’, common in many countries, including New Zealand. Waikiki, in the near past, was a bay of crystal clear, lime green water, revealing its many reefs along the bottom of the bay. The milky residue is the result of a white silt that continues to leach into the water from the sand deposited there as ‘beach nourishment’, obscuring and destroying the reefs and the marine life dependent on them. (Gradually, Hawaii’s iconic beaches are disappearing. Most beaches on the state’s three largest islands are eroding, and the erosion is likely to accelerate as sea levels rise.)

Beneath this sublime scene of human fantasy, is the denial of a recognition of the bioloical impact of beach nourishment, and how the creation of an ‘idyllic’ (utopian) vacation environment is a severely destructive action. Beach nourishment destroys the entire nearshore marine ecosystem affecting birds, nearshore fish, and invertebrates. Orrin H. Pilkey in his book, “The Last Beach” explains that these attempts are doomed to failure and that, “to save beaches we must let beaches go where and how they want”.

Carters work references artists like Richard Misrach and Andreas Gursky in asking fresh questions about our interactions with the natural world, and bodies of water in particular, and what these interactions mean both for our interior, personal worlds as well as our consumerist cultural and social structures as our natural world continues to be challenged under our ‘stewardship’.

Drifting #1 Pataua, 2014

Finalist of the 23rd Wallace Art Awards 2014

Water and more specifically the ocean is the source of inspiration for body of work I am currently working on. The ideas are inspired by Aotearoa’s identity as an ecologically- isolated territory discovered by ocean borne navigators who looked to the skies and ocean currents to locate themselves. There is an imaginative and kinesthetic curiosity as I float alone in the ocean, adrift. The work seeks to reframe this anonymous landscape through the intimate perspective of being semi submerged and anchor-less, moved by the swell and currents. As a way of reflecting this movement and vulnerable positioning of the body in the ocean ‘Drifting’ 2014 was created by merging three photographs each taken several minutes apart to reflect the movement of the body in relationship to the slower transforming cloud formation in the sky. When the body is immersed in these liquid environments there is an inherent sensuous vulnerability, a sense of destabilization and disorientation which can act to “…break the skin of existence in order to lay bare the generating axis of it’s becoming” (Kearney, 1998, p.125). These places can help to rupture our expectations of our existence, and how our bodies operate in the world to emerge again with new frames of reference. Through this potentially psychologically compelling encounter the work also explores the relativities of time and space, the ambiguous potentiality that occurs where surfaces blur and mingle, to restore mystery and a sensuousness of vision, to draw out the sublime from the familiar. This sublime is redolent with what James Elkins calls ‘the post-modern sublime’. James Elkins in ‘What Photography Is’, describes the post-modern sublime as a “measured chill and reverberating emptiness”. (Elkins, 2011, P.77/78). This post-modern sublime relates to inherent qualities within these spaces which are in part determined by the vastness of nature, but also by weather and light. In addition, the work seeks to approach these different liquid environments from new positions and perspectives that give the work sufficient force and vividness to achieve an impact, described by Baas and Jacob, as able to “momentarily cut through the ongoing conceptual mind” (Baas & Jacob, 2004, p.43). to promote greater reflection and contemplation

The project has explored spaces of water within Waitemata Harbor and a multitude of locations off the east and west coast of the north island, with the south island coast as the next proposed location. During the filming the project has encountered ecological and socio-political questions relating to use of natural resources. These concerns are present in varying degrees within the work. However the emphasis is to create a space of affect, a visceral physical response to bodies of water.